A Microarchitecture Retrospective

As a student who did reasonably well in Patt's Microarchitecture class, I have been asked by many bright undergraduate students if the class is right for them. In every talk I have had, I don't think I have ever endorsed 'EE 382N: Microarchitecture' (Which I will now refer to as microarch to disambiguate it from the concept) as a class they should take. This is despite the fact that I personally, would take the class again if I were to redo my masters degree.

When giving advice, my first question is usually 'Why?'. This is as it helps to understand where someone is coming from. Often, when I ask 'why microarch?' the response is 'I want to learn X' or 'I want to X'. My response is usually that microarch does not teach X very well. At which point we look at the registrar and I recommend some of the great classes at UT which teach X better. For some common X, I might say:

- Microarchitecture --> CS395T: Prediction Mechanisms in Computer Architecture

- How computers work --> CS 380L Advanced Operating Systems

- How to get high performance --> EE 382N - 20-Comp Arch: Parallelism/Locality

- How to build an IC/CPU --> EE 460R, Introduction to VLSI Design

- How to make X work --> EE 382M – Verification of Digital Systems

To this day, I don't think this has convinced anyone to change course. The initial stated motivation was inaccurate. After a bit more talking, we usually get into one of three core motivators: Desperation, Prestige, Challenge. Desperation to get a job, hoping that microarch will tip the scales. Prestige that comes from doing something that is known to be difficult. Or just the challenge seeking behavior that gets a student into a good school in the first place. These motivations are somewhat similar, especially in the way they make you shrug off warnings of difficulty. The warnings only add to the allure.

To be clear, Microarch is difficult. Just in a 'reducing a pile of boulders into dust' way. I think detaching from the class when describing the journey will help make the feelings this class invokes more clear. Imagine you sign up to just 'reduce a pile of boulders into dust'.

You don't know a lot about boulders, but how hard can it really be to get a couple? You have spent a lot of time on the beach, and know a LOT about sand after all. People say microarch is difficult, so you and your friends form a team eyes wide open.

As it turns out, finding boulders is very difficult. Once you do find a boulder, it is much larger than your time with sand led you to believe. The implicit concepts of a plan you had to 'just make a pile' when first considering the problem immediately proves inadequate. So you start trying to reduce scope, except scope is what brought you here. You are sure the next boulder will be easier anyways.

Needless to say, it takes a long time to get the project to 'step 1: pile of boulders'.

Eager to make up time you are tempted to jump into the real work. Although you aren't allowed to use external tools, you are given a hammer. Swinging a hammer is easy. At first, there is a certain visceral pleasure in breaking larger rocks into smaller rocks. Eventually you realize the costs. Your arms ache. You haven't slept. Your other responsibilities are catching up with you. In my year, everyone I knew who took the class got dumped including me. The recursive nature of the problem becomes painfully apparent. Each rock keeps becoming two. Smaller rocks much easier to break.You wish for a better tools. But there is so little time. The best you can do is attach a large rock to the hammer. It is harder to lift, but at least it takes fewer swings. Besides, you would have to stop smashing rocks to get a better tool. So, over and over and over and over again down the hammer comes.

At the end of it, when you have reduced a hill into a sand pit, you will feel pride, loss, and exhaustion. Was it a good use of your limited life? Well, it depends how much you enjoy having sand and how little you value your time.

Stepping away from the story, I will discuss some of the high level issues more concretely:- The class is not very applicable. Although timing is important, the way the class has you create circuits is not realistic or necessary. A good analogy would be learning a lot about instruction encodings to prepare for a programming position. What you learn might be useful on limited regions of hot code, but is still at a lower level than needed to work effectively*.

- The lack of structure in the class makes it hard for students:

- To estimate how much work the class will take. This also means its hard to split work equitably and work efficiently in parallel.

- To create good interfaces between modules, especially to the specificity that correct function requires without adding extra latency

- To tell if you have done things correctly until any errors are weeks/months old. Especially as your tests don't have firm grounding

- To avoid errors causing large setbacks. If your home brew tooling is not adaptable, even simple errors might require a significant amount of reworking or even redesigning to fix. The boundaries you draw can be incorrect to an unbounded degree

- Structural Verilog takes a certain mindset to write that is not really taught at UT. We spend very little time at the logic gate level other than 316, and the techniques we learn there do not scale well to larger designs. Instead we tend to focus on programming, with some higher level behavioral verilog in the program. This program focus makes sense, as synthesis tools mean behavioral verilog often produces better results than naive structural verilog.

- You are making something with a lot more moving parts than you might be used to. At the same time, the class to a large degree assumes a lot of knowledge as a prerequisite that it will make no effort to teach you.

- The libraries used by the class have some primitives (Notably the ALU&memory cells) which have bugs/are hard to interface with correctly due to code quality. I was familiar with Verilog from work and research, but still, the memory cells were an entire exercise to understand without resorting to just trial and error.

- The class has assignments that set you on a pace too slow to actually finish the class on time. Lectures and assignments are often more distracting than useful despite the TA's best efforts. The lectures are not directly helpful to the project, but the exam and especially the oral exam are just a memorization test of the lectures.

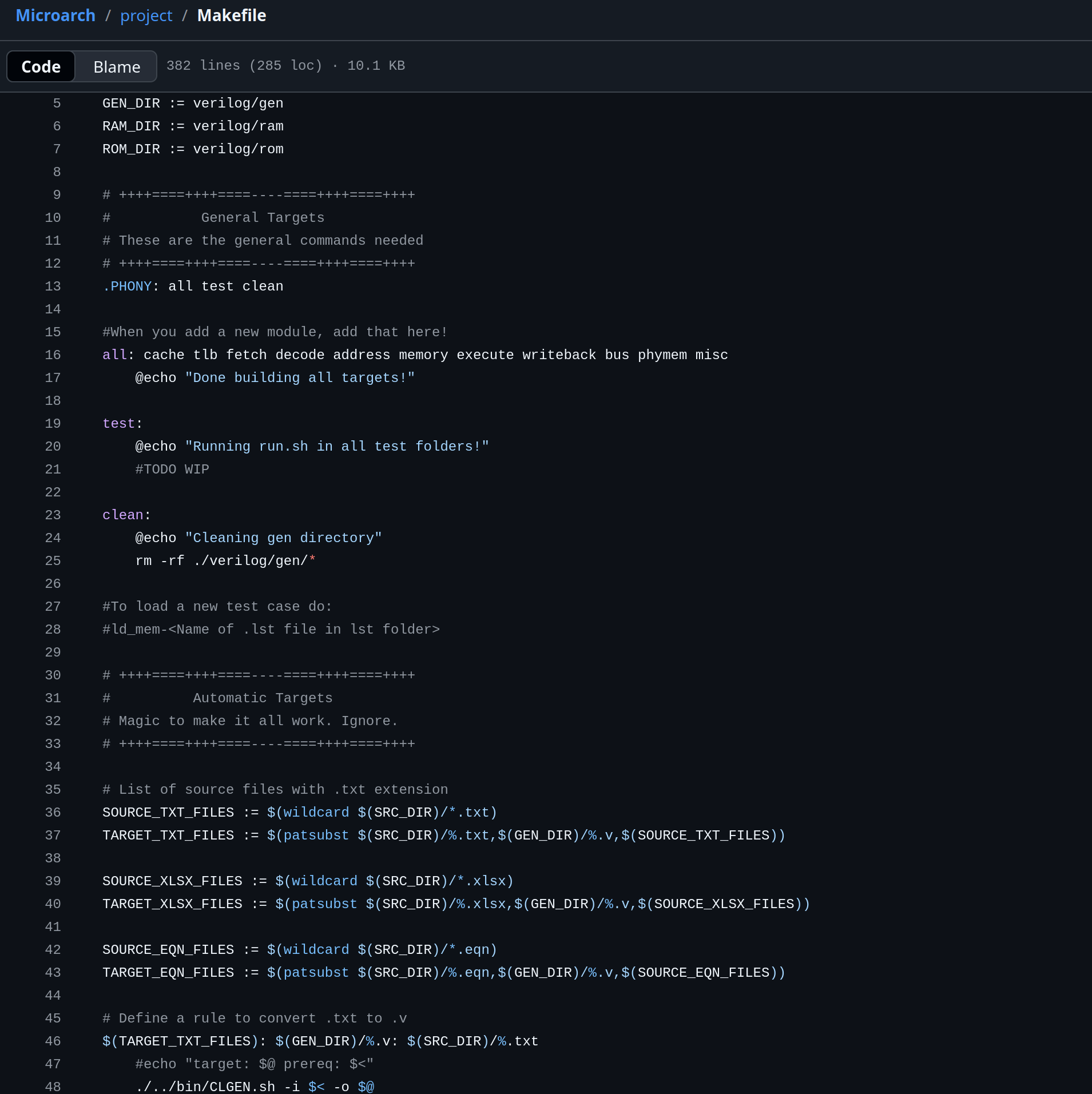

Stepping back from the problem, the project also just is a lot of work. Without getting into the low-level design that would be academic dishonesty, there are a few things I can show.

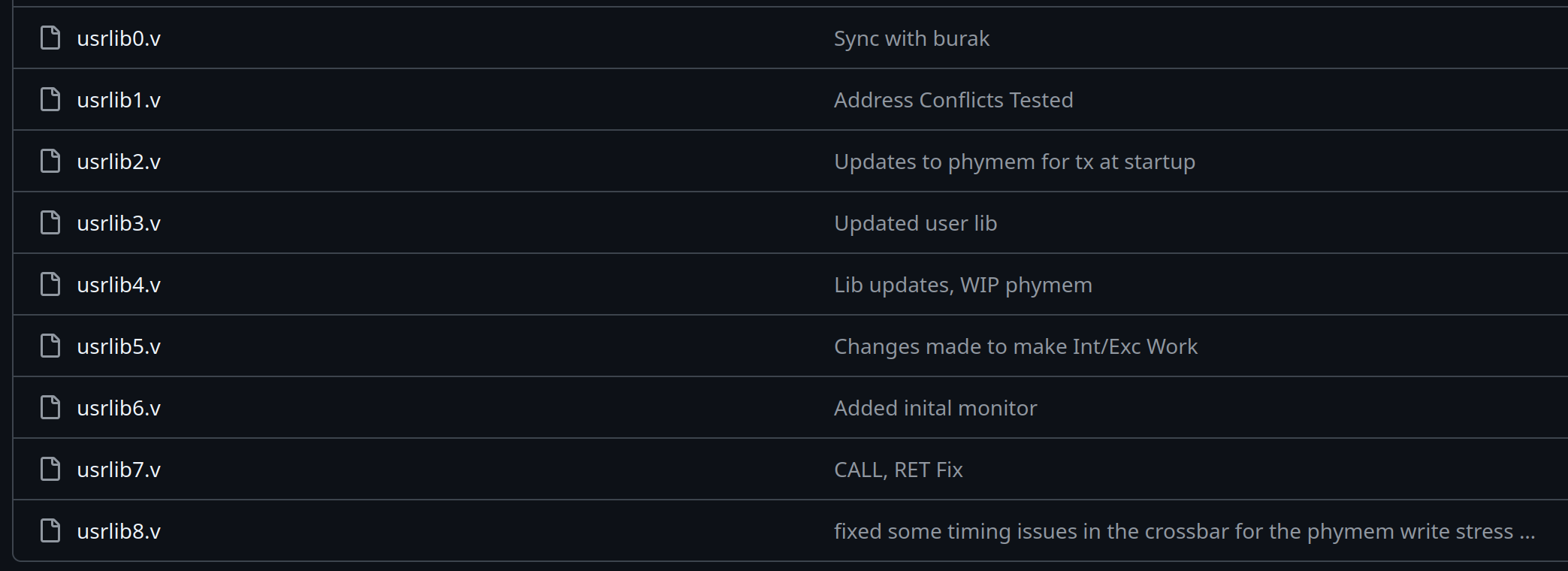

One thing is the structural Verilog libraries we had. You will always need to write a fair amount of handwritten code to at least glue blocks together. Here are 8 libraries that we made. Why? There were the normal adders, and optimized implementations of large gates (4+ input xor/xnor/etc). It was also common that we needed arbitrary size muxes/tristates/magnitude&equality comparators/registers/etc. For functional reasons, it also was clear we needed clock relative strobe/pulse/delay generators of arbitrary timing. Creating these abstractions saved a lot of time, and helped us meet timing. Otherwise, we would have to make this simple bespoke blocks. For this to have been worth it implies that there was a lot of verilog written.

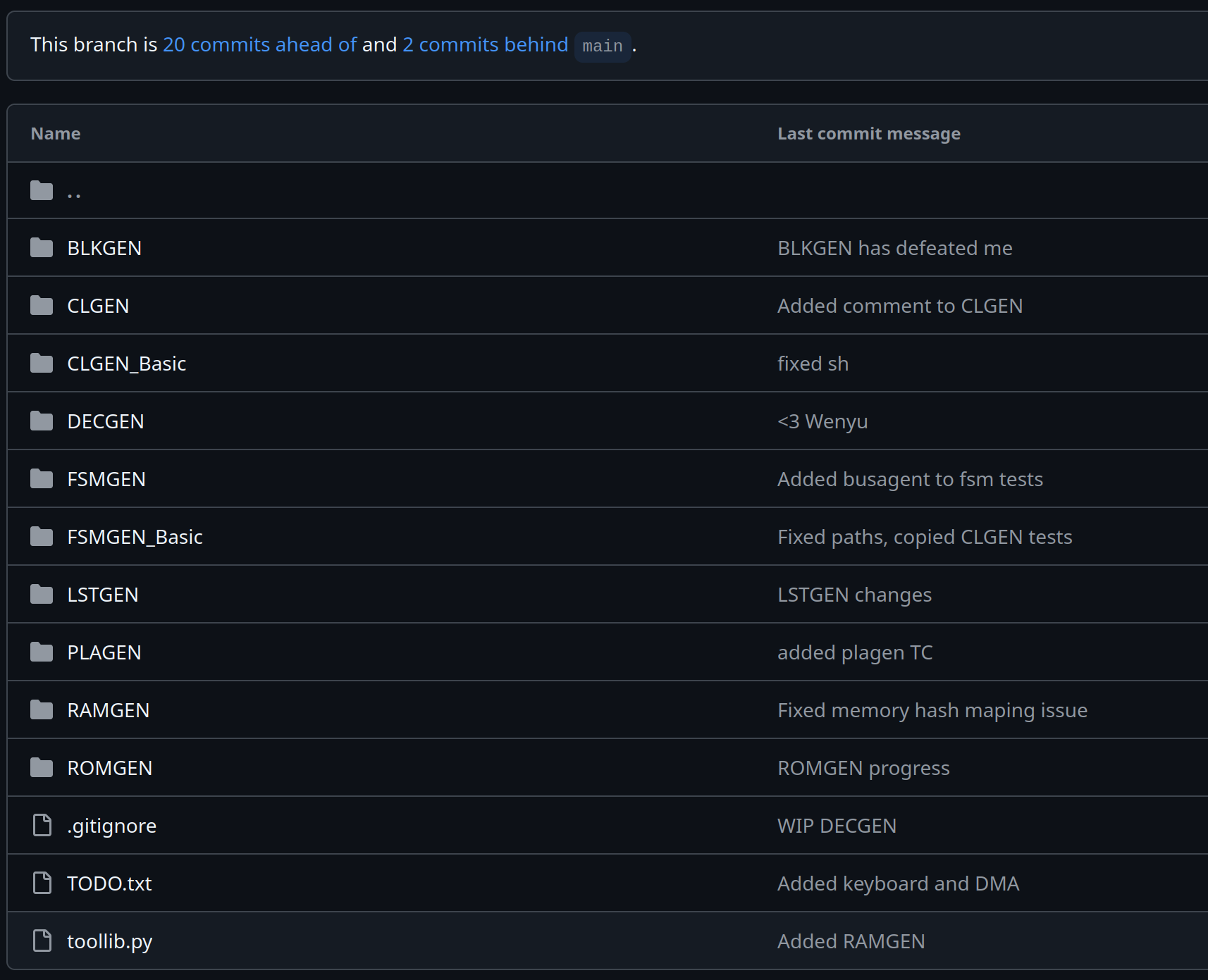

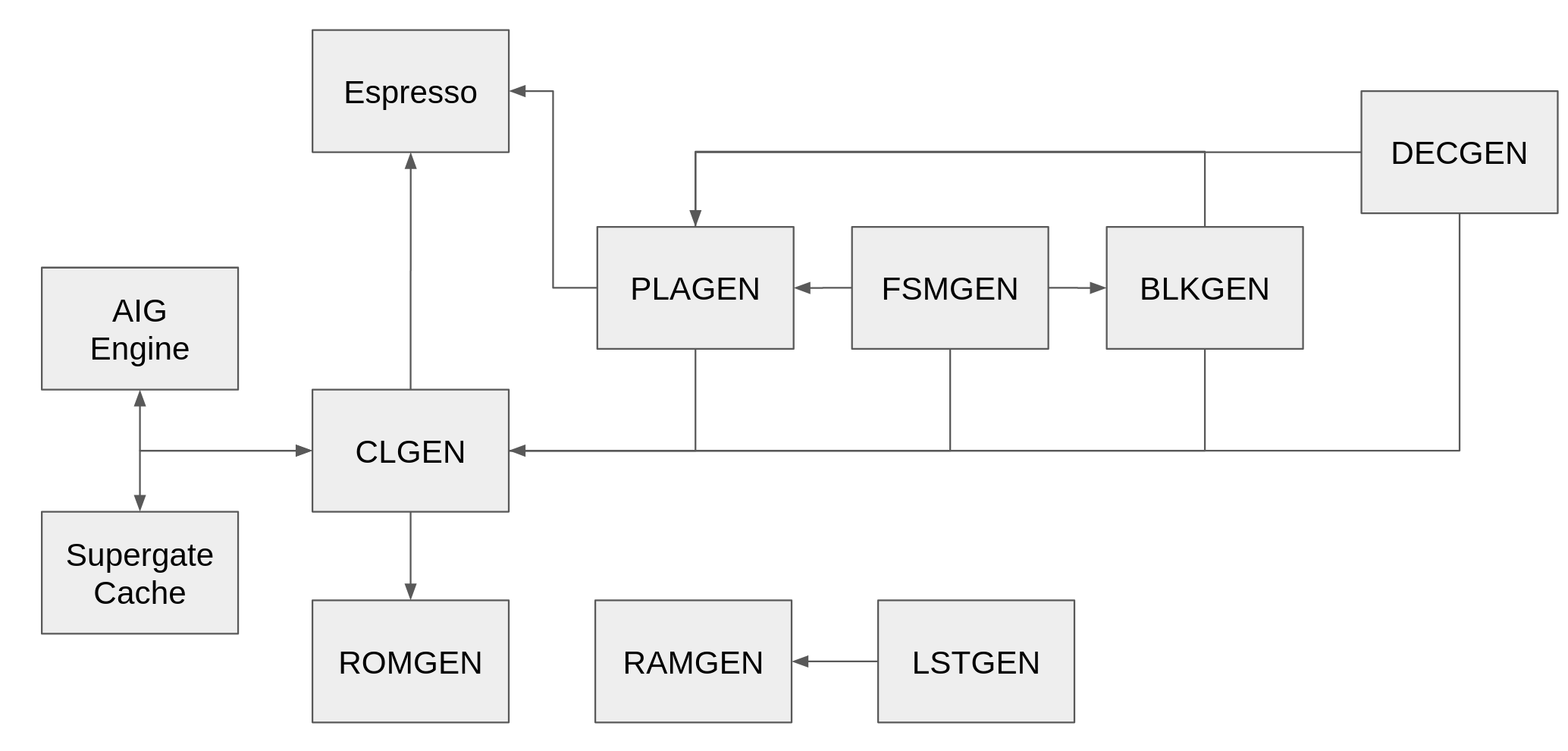

Our team also had to create a lot of generators to make errors easier to fix (Same block in two places vs two instances of the same bug), make interfaces more regular, and reduce the need to write code by hand. The only tool you are given is Espresso, a logic minimization tool. Espresso, critically, is the only tested tool you get to use; everything else you build.

The call relationship is shown above. We spent a lot of time on tooling so that our design would be as flexible as possible. All of these tools had bugs that needed to be fixed. My group mate Wenyu said the worst part of debugging was finding out you wasted 5 hours for it to just be the tools fault. He had just found an edge-case in the FSMGEN state priority logic. We tried our best to write test benches for the tools, but the tests were mainly regression tests rather than future looking tests.

The size of our design meant these tools had to be optimized to be fast. Our decoder generator took over 8 hours to synthesize the decoder block on the first run of about 6% of the ISA, in the end it took less than 15 minutes to synthesize the full ISA. Our final AIG based CLGEN beat our initial version by 3X in terms of latency, when the AIG versions already was strictly better than the pure espresso version. The AIG version finds common nodes between outputs and also maps pre-computed 'super gates' onto the function instead of just minimizing the number of logical miniterms.

PLAGEN allowed Verilog style bus expressions to be synthesized. BLKGEN created optimal basic structures for the design. RAMGEN and LSTGEN worked together to create the DRAM and load the program into it. ROMGEN allowed for certain functions to have even lower delay than what CLGEN could create alone.

These tools were used to create over 100 unique verilog blocks for the design (Not including the handwritten parameterized library blocks). Often when a tool had a bug fix, we wanted to regenerate everything that the tool had generated including cached files. We also ended up needed scripts to make sure that the environment had all of our tooling setup properly and a functional simulator for automated testing as we were using both our laptops and LRC machines which had VCS licenses, on laptops the tool chain automatically switched from VCS to Icarus. Icarus (And Vivado surprisingly) had a trade-off of not implementing all required timing primitives directly causing false successes, but the Icarus simulator didn't require a license server to run.

The largest of these auto-generated files is likely the decoder stage of the pipeline, which came in at roughly 130 thousand lines long (debugging this stage was type III fun**). The decoder had a large number of input positions due to the variable length of x86 and mapped any instruction into VLIW-like control signals for the rest of the core while also extracting any arguments from the instruction in a single cycle.

We had over 40 hand-written design blocks. Thanks to the generated blocks, the median file length is only 150 lines of structural verilog (Although some of these files are well over 500 lines of assignments long). Its important to keep in mind, that all of this more or less has to 'just work' the first time.

The timeline is extremely tight, especially if you want to make something good. Not to mention things always go wrong. I remember my car broke down a couple weeks earlier. It felt like the worst possible time, as I didn't even have the time to get it towed home. I shifted it into neutral and pushed it into a hotel parking lot from the side of the highway. To get to school I would take the bus after carpooling closer to Austin. The timing couldn't have been worse.

You are only meant to have one final checkout for the project. The reasoning being that seeing the test cases gives away the problem. Once you see the exact assembly your core needs to run, it is too tempting to make a CPU just barely capable of running that exact pattern. This was especially true of the performance test cases.

I was worried about how I was going to make the 20 mile trip to checkout, never mind how I would get back home afterwords; after all I had already slept enough days on campus for it to barely register for just one night. We checked out on the day before grades were due to be returned to the registrar. We started checkout with our TA Kayvan Mansoorshahi as soon as I got to campus at Noon.

We blew through the timeline I expected with test cases, missing my 9PM ride home. Still, Kayvan said that our checkout went 'Pretty smoothly all things considered' despite the fact we finished at 3AM. I will note, we had the opportunity to take a break from checkout in-between test cases. Maybe we would have taken a break if it wasn't the last day to get the project over the finish line. In the end, we were the only team to finish by the original deadline, and so we didn't need an incomplete to try to finish the class.

I think part of why it went smoothly was our emphasis on testing. We had scripts which could run our over 30 test-benches to validate high level blocks that had defined IO behavior. My favorite was the memory fuzzer, which simulated 3 bus agents Reading/Writing to DRAM at the same time. This found several functional bugs in the DRAM controller, and saved us from any DRAM issues in checkout. Wenyu's favorite was the top level test bench that ran actual assembly through the core, and which we all sat in front of for more than two weeks before checkout. Ann's favorite was probably the DMA test bench, as it had the least problems and was one of the last things to put us over the finish line.

We had pulled full days working on this class for weeks, not to mention consistent effort since the team formed. I also liked to think that I knew a lot about CPUs having designed one from scratch 4 years prior for fun, and having worked as an intern in the industry. Still, I don't think I would have been able to finish on time without my teammates Wenyu Zhu and Anne (Chieh-an) Chen.

In the end, I think the most important thing 'EE 382N: Microarchitecture' teaches is not the content. You don't learn much about Microarchitecture and much less about anything modern. Instead, for better or worse, you learn how to push your limits. Sometimes seeing just how much you can do is fun.

* - I will admit however, that the low level at the class will force you to remove gaps from your knowledge. There was a misconception held in the beginning of the project that it was feasible to read from a register file in the middle of a cycle for example. This caused several stages to require redesigns once we noticed that assumption had made it into our docs.

** - This is admittedly a niche taxonomy I learned from my colleagues who go bouldering (hahaha...), but it goes: Type I fun -> Fun in the moment, Type II fun -> Fun with hindsight, Type III fun -> Not fun in the moment, not fun in hindsight, but a fun story

Recent Updates

A Microarchitecture Retrospective

Microarchitecture is Yale Patt's signature class and widely considered the hardest course offered by the department. But is it the best place to learn CPU design, when the assignment makes you balance design complexity and tooling development against a... Read More

Just like cats

Sometimes I look at my sisters cat and wonder what he can understand. My sister's cat is named Boba. He is a good sort of fellow, well behaved, polite... endlessly hungry. Often, I look at him and wonder what he sees. Of course his vision is different ... Read More

More Than a Robot Couch

Fundamentally, engineering is just about choosing whats best. The hard part is just figuring out what is best. Getting caught up in my regrets used to feel like progress. After all, introspection is the first step to improvement. While important, intro... Read More

My Custom 8-Bit CPU

How I learned to let go of small things like ‘value proposition’, ‘opportunity cost’ and ‘reason’ in order to embrace the transistor. In the later half of my internship at AMD in 2019, I was struck by the Muse. I had just seen the Monster 6502, which i... Read More

On The Balance Of Words

Being clear about what you mean is a skill, but being clear while avoiding accountability for the consequences is a profession Everybody knows that lying is wrong. Or at the very least, that lying too much will get you in trouble. Everybody also knows ... Read More

Text Stripping Tool

This is a simple tool that I made to strip HTML out of transcripts I was copying and pasting. I also ocasionally run into situations where there are many superscripts and it gets tedious to remove them all by hand. Just note that the tool is a little i... Read More

Micro-Benchmarking Compiler Auto-Vectorization

A colleague sent me a link. Hours later, I was still deep in a rabbit hole of assembly, auto-vectorization, and benchmarking GCC vs. Clang. One of my long time colleagues Brendan sent me a link that you can view HERE. Naturally, I opened it as soon as ... Read More

This page has the following tags: Thoughts, University, Projects